Forgiveness: How It’s Truly a Path to Our Own Freedom

Overview: Forgiveness, the profound letting go of grievances, provides a key to reclaiming the essential self and building healthy relationships. Ironically, each type holds specific resistance’s to forgiveness which are tied to the type’s survival strategy. The barriers to forgiveness, the costs of holding grievances and resentments, and how the barriers to forgiveness be worked with are all explored here. In reading and responding to this blog, bring an open mind, heart, and spirit and an example of something or someone (which could be yourself) you need to forgive.

By David Daniels, M.D.

Without forgiveness, life is governed by an endless cycle of resentment and retaliation.” — Roberto Assogioli

Forgiveness is not an occasional act; it is a permanent attitude.” — Martin Luther King, Jr.

If you are bitter at heart, sugar in the mouth will not help you.” — Yiddish Proverb

Forgiveness is an absolute necessity for continued human existence.” — Desmond Tutu

In working with inmates for the Enneagram Prison Project (EPP), I rediscovered how, “We are all prisoners of our own making,” as Susan Olesek[1] puts it. And a key to remaining in this “self-imprisonment” is the lack of forgiveness. This is key to both those incarcerated as well as for the rest of us.

First, we need to define forgiveness as both the pardoning of offenses and the releasing from resentments. And here’s a critical distinction: Pardoning an offense does not mean we deem the offense as unimportant nor deny the consequences, but rather, an allowing for penalties to be applied in a way that is respectful to both offenders and pardoners.

Next, we need to release our resentments. This can only begin when we forgive ourselves. Oddly enough, it’s self-forgiveness that gives us a run for our money. To forgive our self “for not knowing better,” or, “for not listening to our gut instinct when it told us ‘not to’ do something,” or, “for being blindsided and hurt by someone,” or “for hurting someone else when we know we did it willfully,” — I could go on and on. But forgiving the self is the first critical step to releasing the stored up resentments held against self and other, that keeps us “stuck” as well as keeps us from the critical learning available through understanding and self-witnessing, all of which refusing to forgive “prevents.”

By forgiving the self, which can turn into great learning and understanding to do better next time, we release ourselves from the resentment that is fueled by unhealthy forms of anger. Consequently, healthy forms of anger allows us to undertake actions that affirm our own respect for personal boundaries, self-control, and the opening of the heart to better and more protectively regard the esteem of self and others.

By forgiving the self, which can turn into great learning and understanding to do better next time, we release ourselves from the resentment that is fueled by unhealthy forms of anger. Consequently, healthy forms of anger allows us to undertake actions that affirm our own respect for personal boundaries, self-control, and the opening of the heart to better and more protectively regard the esteem of self and others.

True forgiveness involves a liberation from the personal confinement of harboring resentment. Sadly though, for the most part, our United States justice system operates from a model of punishment and the holding of resentments, it’s built right into not only the sentencing of those “labeled criminals” all the way to the treatment of them while incarcerated.

What we’ve come to learn is that when we strip human beings of their identity, put them in black-and-white, bright orange or dark blue prison clothing, confine them to small spaces, regiment them, restrict their contact with the world outside behind barb-wired electrical fences, and treat them as ‘children of a lesser God,’ we are in fact operating from antipathy. Unfortunately, this is not just harmful to those incarcerated — those who are long hurting in the first place, but to all of us, including correctional officers, judges, district attorneys and case workers, those individuals hovering close to such an aversive-to-humanity system. The type of anger that insidiously simmers underneath resentments, antipathy, and punishments harms the body, the heart, and the soul of all those in contact with it.

What we’ve come to learn is that when we strip human beings of their identity, put them in black-and-white, bright orange or dark blue prison clothing, confine them to small spaces, regiment them, restrict their contact with the world outside behind barb-wired electrical fences, and treat them as ‘children of a lesser God,’ we are in fact operating from antipathy. Unfortunately, this is not just harmful to those incarcerated — those who are long hurting in the first place, but to all of us, including correctional officers, judges, district attorneys and case workers, those individuals hovering close to such an aversive-to-humanity system. The type of anger that insidiously simmers underneath resentments, antipathy, and punishments harms the body, the heart, and the soul of all those in contact with it.

So, why do we hold on to resentments? And why have we built a correctional system based on a model that punishes, resents, and berates others and in the long run, ourselves and our society too? Seems like a lot of damage-in-the-making, if you ask me…

I tend to think that we hold onto resentments because it’s our way of trying to protect ourselves from getting harmed again. Society too. If we collectively harbor resentment, hold on to anger, and endorse punishments, those causing harm will stop. Well, on the surface this sounds good and makes sense so we “Carry on!” But if you look closely, you’ll see that something else is going on.

“Punishment doesn’t heal. It enrages. Resentment doesn’t stop harm. It only poisons its host and restricts and imprisons hearts.” — David Daniels, M.D.

NOT forgiving, a form of punishing, is based on the knowing of perceived threat and the holding on to what happened, so it “won’t ever happen again.” Well, guess what? It can happen again, but only now we’re exhausted by carrying resentment day in and day out and have lost vital pieces of ourselves and our self-expression the entire time we were resentful as well.

We hold on to resentments to protect what we are identified with or attached to from being violated. This gets us down to very personal, basic violations, even though we mostly are not conscious of them or even deny their existence. Moreover, holding on to outward behaviors that manifest resentments perpetuates our unconscious attachment to what could be violated within us.

What Exactly is Forgiveness?

Getting back to forgiveness; it does not mean condoning, capitulating, or concurring with what has caused any level of resentment. Nor is it resignation, forgetting, or permitting what we define as odious behavior. It’s important to deeply understand that the forgiveness that releases us from resentments is the path to our own freedom and our own healthy behavior.

What’s Good About Not Forgiving?

But to have some compassion and understanding for ourselves, and in order to learn to “let go” of resentments and an unwillingness to forgive, let’s first ask this question: What’s the value of staying resentful? There’s always a benefit to behavior, and that needs to be respected too. Resentments can give us a sense of moral superiority. A sense of power. It’s an action step that sets out to protect our self-esteem and our boundaries. Not forgiving also provides deep insights into ourselves as it can reveal key issues, deeply embedded pain, and the attempt to show our own strength and autonomy.

However as Robereto Assogiolie once said and I quote, “Without forgiveness, life is governed by an endless cycle of resentment and retaliation.”

What Does Forgiveness Give Us?

Now, let’s ask a second question: What’s the value of forgiveness? Forgiveness involves healing. It involves freeing ourselves of the stress of ongoing anger and the underlying intrapersonal suffering we may be enduring as a result. Even more importantly, forgiveness frees energy – our own life force – and the power generated by freeing our own life force enhances self-esteem and, in turn, opens our heart again to self and others.

Forgiveness and Personal Power

Forgiveness is possible once we understand the power of it. Forgiveness is an act of freewill, it’s a power move on behalf of ourselves and is rich in deeper meanings and tremendous lessons. Forgiveness honors that we are a separate self, and it’s only “we” who can respect our boundaries and autonomy. Forgiveness represents that we realize the longer-term cost of harboring anger and resentments and fully embody the power of their release.

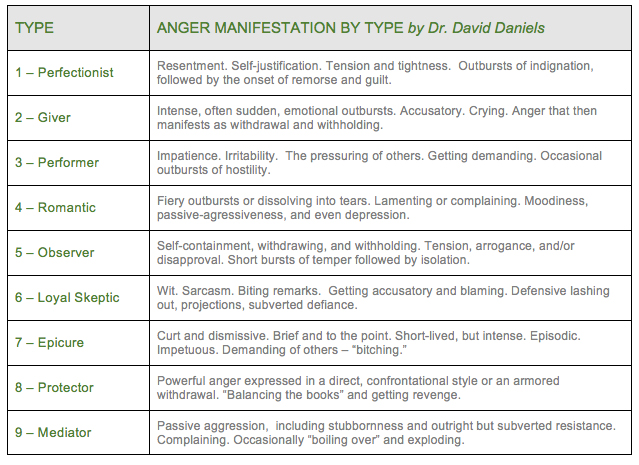

Enneagram Type Structure and How We “ANGER UP”

Each Enneagram type expresses and/or harbors anger and resentment in particular, predictable ways. Here are descriptions of each type’s definitive “anger-resentment” pattern, which is often a cover for the suffering and perceptions of deficiency within.

Learning to Let It Go

The most important step we can take in learning how to release ourselves from chronic anger and resentment and move into states of forgiveness involves the development of the inner-witness, of a good self-observation practice, which is the first-step training toward open-hearted receptivity. We have to be able to contact the resentment and the anger itself; where it’s residing in the body; when, how, and where it gets triggered; and how it’s impacting us day by day. This takes inner witnessing to track honestly.

Also, it’s incredibly useful knowing your Enneagram type’s more predictable and habitual manifestations of anger and resentment, which I’ve detailed for you above. For each type, you can see how the type structure is trying its best to ensure a separate, independent, and unharmed self.

Furthermore, through self-observation, self-witnessing, we have the power to not only “see” our behaviors, but to manage and change our behavior as well; and, yes, release into understanding and then forgiveness. This is the very process that deepens our capacity for discernment and personal change. It includes knowing when and how to take affirmative action, or when to just let go of outmoded, no-longer productive beliefs and relax into “presence.” What’s actually, genuinely, called for right now?

Forgiveness is not a copout. It’s a conscious, powerful practice. Forgiveness is actually one of the most powerful paths to personal freedom and well-being I’ve ever witnessed as well as have experienced myself.

Take a few quiet minutes to reflect on the concept and possibility of forgiveness in your own life…

[1] Susan Olesek is the founder of the Enneagram Prison Project (EPP). www.enneagramprisonproject.org